A goal statement is a succinctly written version of your intervention plan used to convey the information essential to describing the treatment target, the intervention procedures and the outcome criteria. Goal statements can be used to address the spectrum of your client’s needs: the acquisition of target behavior in a specific therapy activity of a treatment outcome, the emergence of a generalized targeted skill or functional outcome probed outside of therapy, or the achievement of an ultimate outcome leading to the completion of the client’s therapy program. In this section, I will discuss the relationship between intervention plan and goal statement, influences on writing goal statements, and how to compose a goal statement.

Goal Statement versus an Intervention Plan

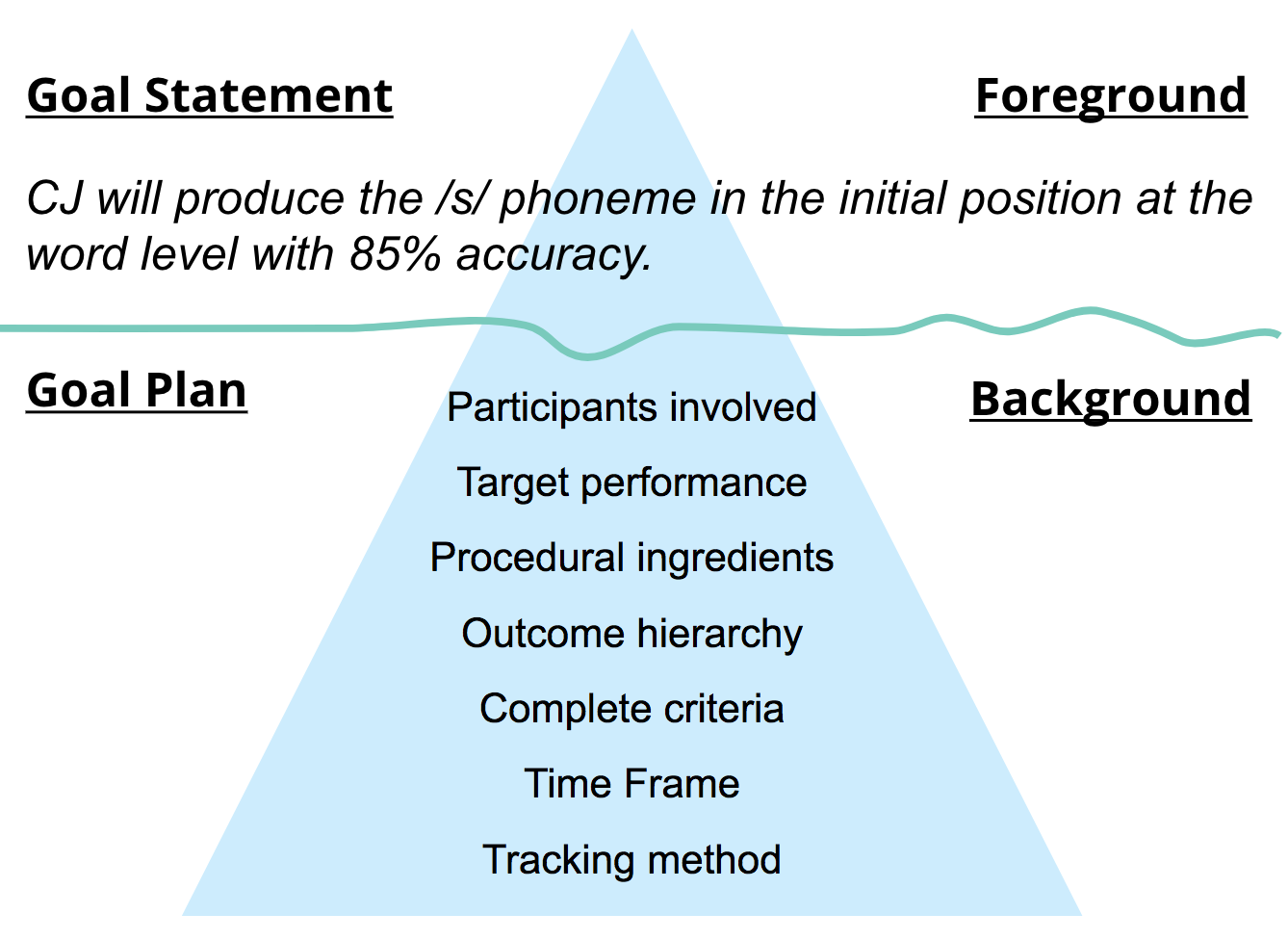

As you are writing your therapy goal statement, it is important to keep in mind the difference between your intervention plan and the goal statement. Your intervention plan contains all the operative elements of your intervention approach. Some of those elements appear in the foreground, that is, written up as a goal statement. But most of the information about your goal will reside in the background, in the intervention plan. The iceberg model to the right visually illustrates this relationship. The goal statement provides a concisely written description of the treatment target and expected outcome success criteria (i.e., tip of the iceberg). However, it is incomplete compared to the intervention plan, (i.e., below the water line), requiring the reader to infer much of the information needed to understand and carry out the proposed intervention.

A minimum of 3 elements are necessary to construct a goal statement, based on the treatment components mentioned in the last section. They are:

- the participant (JJ will…),

- the target performance . (…correctly produce the /s/ phoneme in initial position…),

- and criteria (…85% of the time).

Other information such as condition, context, time frame, the client’s original status may be included in a goal statement depending on its intended use. Several factors will influence the content and writing style of your goal statement. First, you will want to fulfill the needs of the intended audience of the goal statement. Will the audience just include yourself, your supervisors, or other health professionals? Each audience member may need certain details in order to ensure their understanding and abilities to communicate this with others. The agency that you work for may also require specific information and a format for writing the goal statement. Finally, the content and style of the goal statement will also be influenced by your own level of experience and reasons for writing the goal in the first place. If you are just starting out, your goal may need to be written out in greater detail to help you structure a new therapy approach, as well as address the requirements of your clinical supervisor. As you gain more experience and independence, you may decide to use the goal statement more strategically, including information that is different from your standard practice.

Composing a Goal Statement

Here is an example of a goal statement, first presented in sentence form, then divided into its goal components:

PS will correctly transcribe important information components concerning an event, delivered by phone, 4/5 times per session.

Below is the same therapy goal statement divided into its component categories and accompanied by other important treatment goal information, not included in the statement.

| Components | Foreground: Tx Goal Statement |

Background: Unwritten Components |

|---|---|---|

| Participant | PS | With the therapist and therapy assistant on the phone. |

| Target | will correctly transcribe important information components | PS expected to receive, transcribe 4 items provided in the phone message without prompting. Components include (1) name of person who called, (2) name of event, (3) its location, and (4) date and time of event. |

| Context | In the therapy room | |

| Conditions | delivered by phone |

|

| Time Frame | Sessions last 20 minutes, 2 days a week. | |

| Criteria | 4/5 times per session. | For at least two consecutive sessions. |

As you can see, the bulk of the relevant goal information is not included in this statement, and to do so would render the statement long and awkward to read. Unfortunately, without specifying this information, it is easy to forget the specifics of the intervention, or not include this information when reconsidering the course of treatment. In fact, the ingredients of the goal are more important than the statement, and it is advisable to develop a method for collecting and listing them so that you can refer back to them as you make decisions about your client’s progress.

SMART Goals

Not to be confused with the specific implementation of Bovend’Eerdt, et al., (2009) SMART goal evaluation framework described above, this SMART goal formulation refers to a broad set of criteria for setting objectives, and the acronym is often transformed to meet the needs of specific organizations and initiatives (Wikipedia). In the education and clinical domains, SMART goals provide a mnemonic-based framework to remind clinicians about goal writing values (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Accountable, Relevant, Timely). It is important to note that the SMART goals are not goal components, but rather heuristics relating to strategic organization and refinement of a general intervention plan into a written plan of action.

Writing in the ASHA Leader, Torres (2013) provides a set of heuristics for dealing with goal writing:

Torres’s presents a series of critical questions, a sort of interface between your intervention plan and goal statement, to help you consider the important element in developing the actionable steps in your intervention plan. These questions are relevant for finding places to initiate treatment in your overall intervention plan organization, as well as refining a specific objective. This process should work with any of the intervention plan approaches presented in the previous section.

Critical SMART Goal Questions (based on Torres (2013)

This category focuses on most of the intellectual work around goal writing: identifying and refining specific goals, procedural ingredients, underlying causal mechanisms and goal sequences. Review your intervention plan with these questions until you have the answers:

- What are the client’s communicative strengths and weaknesses?

- What are the underlying skills that appear to be mediating the client’s weaknesses/the strengths?

- Which of client’s skills can be used to compensate for deficiencies?

- Which skills that are lacking can I help the client attain?

- What do I want to work on first? Why do you want to work on that first?

- What are the tasks you will have the client complete or engage in, to work on the skill?

- What supports will you provide for the client?

-

The Measurable category focuses on how you will determine if your client is achieving their goal or not? Adjust your goal specifics until you can measure them. Chapter 5 deals with measurement specifics.

- How will you measure progress?

- What criteria will you use to determine if the client is achieving their goal?

- Will the attainment of this goal serve a communicative function for the client or will it just be something you can do with the client?

- Will it serve a purpose in the client’s life considering the limits and ramifications of the diagnosis and his cultural and social needs?

- Does the goal contain a time frame or a date for accomplishing the goal?

- Can the goal be attained in that time frame? If yes….

Conclusion

As discussed above, goal statements are the written counterparts to an intervention plan. It is a concisely written statement expressing the portion of your intervention plan required to fulfill the knowledge needs of your audience and the documentation requirements of your agency. Remember, a goal statement is not the same as an intervention plan/goal. It is important to make this distinction because your intervention plan should contain all the critical elements needed to design, implement and evaluate your intervention. However, the goal statement is one of the principles means to communicate information about your goal. Torres’s SMART goal evaluation process can guide you in organizing your intervention plan to produce optimize your goal statements.